Understanding how a company earns its profits is one of the most important steps in financial analysis. While a traditional income statement shows total profits, it does not clearly tell where those profits come from — whether from running the business efficiently or from financing decisions like borrowing and investing.

That’s where the Reformulated Income Statement comes in.

It separates operational performance from financial structure, giving a clearer picture of the company’s true profitability.

What Is a Reformulated Income Statement?

A reformulated income statement reorganizes the traditional (GAAP) income statement into two distinct parts:

- Operating Income (OI) – profits from the company’s core business activities.

- Net Financial Expense or Income (NFE) – results from financing activities such as interest paid or earned.

By separating these, analysts can see:

- How well the core business generates profit, and

- How much profit (or loss) comes from financing decisions (like using debt or holding investments).

Why Reformulate the Income Statement?

The traditional income statement (under GAAP or IFRS) mixes together:

- Sales revenue

- Operating expenses

- Interest income/expenses

- Unusual or extraordinary items

This makes it hard to identify how much profit came from actual business operations versus how much came from financing or one-time events.

🔍 Reformulation solves this problem by separating:

- Business (operating) activities

- Financing and investing activities

The Two Main Components

1. Operating Income (OI)

This represents income generated from day-to-day business operations — for example:

- Sales of products or services

- Less cost of goods sold (COGS)

- Less operating expenses (marketing, admin, R&D, etc.)

It reflects the performance of the core business and is sometimes called:

Enterprise Income or Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT)

2. Net Financial Expense (NFE)

This comes from financing activities, such as:

- Interest earned on financial investments

- Interest paid on borrowings

- Gains or losses from financial instruments

It shows how the company’s financing decisions affect overall profitability.

The Structure of a Reformulated Statement

The reformulated income statement groups all items into:

- Operating income

- Financial income or expense

And it presents these on a comprehensive basis, meaning it includes even those items that normally appear in the equity section — for example:

- Revaluation gains or losses

- Pension adjustments

- Foreign currency translation gains or losses

These are often called “dirty surplus” items, because they bypass the income statement in traditional reporting but still affect shareholders’ equity.

The Typical GAAP Income Statement (Before Reformulation)

| Section | Examples |

|---|---|

| Revenue | Sales, royalties, rents |

| Cost of Sales | Direct production costs |

| Operating Expenses | Marketing, admin, R&D |

| Special/Nonrecurring Items | Restructuring, litigation, asset sales |

| Interest Income/Expense | Financing items |

| Income Tax | Tax on total income |

| Extraordinary Items | Unusual or discontinued operations |

| Net Income | Bottom-line profit |

Problem:

Everything is mixed together, so we can’t tell whether profits come from operations or financing.

How does the Reformulated Statement fix it?

The Reformulated Comprehensive Income Statement separates two categories:

- Operating Income (before and after tax)

- Net Financial Expense (after tax)

Then, it combines them to arrive at:

Comprehensive Income to Common Shareholders

Simplified Reformulated Layout

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Net Sales | Main revenue from operations |

| – Expenses to generate sales | Cost of sales, marketing, admin |

| = Operating Income (before tax) | Profit from operations before tax |

| – Tax on operating income | Taxes related to operations |

| = Operating Income (after tax) / NOPAT | Core business profit after tax |

| – Net financial expenses (after tax) | Interest cost minus interest income |

| = Comprehensive Income | Final profit attributable to shareholders |

This gives a clear view of:

- Profitability of the business itself

- Effects of financing structure (debt, interest, and investments)

How Tax Is Allocated (Tax Allocation)

In the traditional statement, there’s only one total tax figure.

But after reformulation, we must divide total tax into operating tax and financial tax.

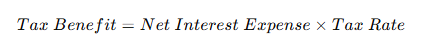

Step 1: Identify the Tax Benefit (or Cost) of Debt

When a company pays interest on loans, it can deduct that interest before calculating taxes.

This creates a tax saving, called the Tax Shield.

Formula:

Example:

If net interest expense = $100 and tax rate = 35%,

then Tax Benefit = $35.

This $35 reduces the tax burden on operations.

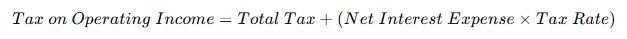

Step 2: Split Total Tax Between Operating and Financial Parts

The tax on operating income is calculated as:

If the company has net interest income (more investments than debt),

then it pays more tax, so the formula flips to reduce the tax on operations.

Two Methods of Tax Allocation

- Top-Down Method – Start from total income and work downward to separate tax on operations and financing.

- Bottom-Up Method – Start from operating income and add taxes related to each part.

Both achieve the same goal: correctly assigning taxes to operating and financial sections for better accuracy.

Example: Reformulating a Simplified Income Statement

Traditional (GAAP) Format:

| Item | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| Sales Revenue | 1,000 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | (600) |

| Operating Expenses | (200) |

| Interest Expense | (50) |

| Income Tax | (45) |

| Net Income | 105 |

Reformulated Version:

| Category | Amount ($) |

|---|---|

| Operating Income (before tax) | 200 |

| – Tax on operating income (35%) | (70) |

| Operating Income (after tax) | 130 |

| – Net Financial Expense (after tax)** | (25) |

| Comprehensive Income | 105 |

This reformulated view clearly shows:

- The business earned $130 after-tax profit from operations.

- Financing reduced profit by $25.

- The company’s total profit to shareholders = $105.

Why Reformulation Matters

| Benefit | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Clarity | Separates core business results from financing results |

| Comparability | Easier to compare firms with different debt structures |

| Better Performance Analysis | Highlights true operating efficiency |

| Link to Valuation | Helps in calculating RNOA (Return on Net Operating Assets) and ROCE (Return on Common Equity) |

| Improved Decision-Making | Managers and investors can see whether returns come from operations or borrowing |

Key Takeaways

- The reformulated income statement dissects profit sources into operating and financing.

- It highlights operational performance independently from financing strategy.

- It adjusts taxes to reflect both parts properly.

- It serves as a foundation for deeper analysis, such as ROCE, RNOA, and value-creation metrics.

Final Thoughts

Reformulating the income statement is like looking at a business through a clearer lens.

Instead of mixing all sources of profit, it shows:

- How much value comes from the business itself, and

- How much comes from financial leverage or investment decisions?

For beginners in accounting or finance, mastering this concept helps in understanding corporate profitability, risk, and value creation far beyond what the traditional income statement can show.